"When the crucified Jesus is called the 'image of the invisible God,' [Col. 1:15] the meaning is that this is God, and God is like this." - Jurgen Moltmann

"Christology must be done in the light of the cross: the full and undiminished deity of God is to be found in the complete helplessness, in the final agony of the crucified Jesus, at the point where no 'divine nature' is to be seen. In faith in Jesus Christ, we recognize as a law of the life of God himself [sic.] a saying of the Lord which Paul applied to his own life ('My strength is made perfect in weakness', 2 Cor. 12:9). Of course the old idea of the immutability of God shatters on this recognition. Christology must take seriously the fact that God himself [sic.] really enters into the suffering of the Son and in so doing is and remains completely God." - Paul Althaus

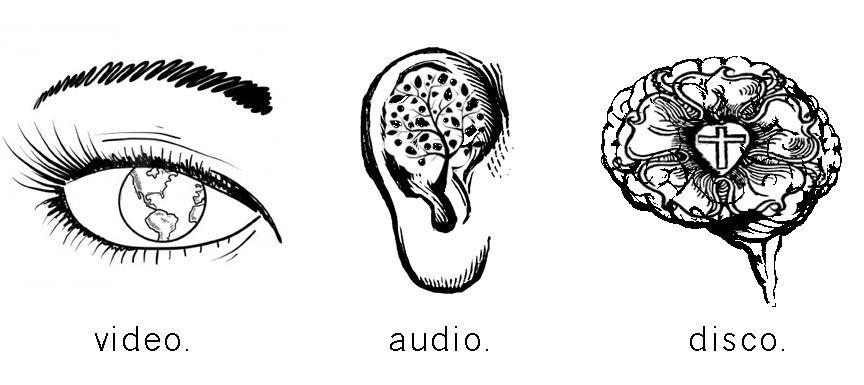

"It is not enough and no use for anyone to know God in his [sic.] glory and his majesty if at the same time he does not know him in the lowliness and shame of his cross... Thus true theology and true knowledge of God lie in Christ the crucified one." - Martin Luther

"If God has reconciled the world to himself [sic.] through the cross, then this means that he has made himself visible in the cross of Christ and, as it were, says to man, 'Here I am!'" - Rudolf Bultmann

"Christians who do not have the feeling that they must flee the crucified Christ have probably not yet understood him in a sufficiently radical way." - Jurgen Moltmann

"To be radical, of course, means to seize a matter at its roots. More radical Christian faith can only mean committing oneself without reserve to the 'crucified God.' This is dangerous. It does not promise the confirmation of one's own conceptions, hopes, and good intentions. It promises first of all the pain of repentance and fundamental change.

It offers no recipe for success. But it brings a confrontation with the truth. It is not positive or constructive, but is in the first instance critical and destructive. It does not bring man into a better harmony with himself and his environment. It does not create a home for him and integrate him into society, but makes him 'homeless' and 'rootless', and liberates him in following Christ who was homeless and rootless.

The 'religion of the cross,' if faith on this basis can ever be so called, does not elevate and edify in the usual sense, but scandalizes; and most of all it scandalizes one's 'co-religionists' in one's own circle. But by this scandal, it brings liberation into a world which is not free.

For ultimately, in a civilization which is constructed on the principle of achievement and enjoyment, and therefore makes pain and death a private matter, excluded from public life, so that in the final issue the world must no longer be experienced as offering resistance, there is nothing so unpopular as for the crucified God to be made a present reality through faith.

It alienates alienated men, who have come to terms with alienation. And yet this faith, with its consequences, is capable of setting men free form their cultural illusions, releasing them from the involvements which blind them, and confronting them with the truth of their existence and their society.

Before there can be correspondence and agreements between faith and the surrounding world, there first must be the painful demonstration of truth in the midst of untruth. In this pain we experience reality outside ourselves, which we have not made or thought for ourselves. The pain arouses a love which can no longer be indifferent, but seeks out its opposite, what is ugly and unworthy of love, in order to love it. This pain breaks down the apathy in which everything is a matter of indifference..." - Jurgen Moltmann

In Matthew's account of Jesus' trial there is a scene when Jesus is stripped and then dressed in a mock king outfit. Donning a purple robe, a crown of thorns and a reed in his right hand, Jesus stands before a public crowd as a joke. The onlookers shout, "Hail, King of the Jews!" and offer satirical bows before him.

What strikes me about this scene is the grandiose irony. But not the kind of irony that we normally think. That is, the irony is not simply that Jesus happens to be the True King "underneath" or "behind" the situation. Rather, the irony is that this powerless king to whom the mockers bow is precisely the image of the invisible God.

Put another way, it is not that the mockers are correct in their mocking the helplessness of Jesus and that in due time they will see his "true" power. No. It is that the mocker's understanding of reality is upside down and they're mocking bows actually reveal the truth about God. The theological truth is revealed in a historical joke.

"But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong." (1 Cor. 1:27)

No comments:

Post a Comment